Cocaine Cowboys opens with a look back at the afternoon of July 11th, 1979, when two men were gunned down at the Crown Liquors store in Miami’s Dadeland Mall over drug dealing turf. The documentary takes it’s name from the colorful label the media slapped on the killers, and when the film moves into it’s opening title credits, the theme music comes courtesy of Jan Hammer. Yes, before Detectives Crockett and Tubbs battled Miami’s drug vices on the screen, we’re reminded that the real-life city had to become awash in white powder. It was smuggled in by the likes of Mickey Munday (who hauled 10 tons of it),

Cocaine Cowboys opens with a look back at the afternoon of July 11th, 1979, when two men were gunned down at the Crown Liquors store in Miami’s Dadeland Mall over drug dealing turf. The documentary takes it’s name from the colorful label the media slapped on the killers, and when the film moves into it’s opening title credits, the theme music comes courtesy of Jan Hammer. Yes, before Detectives Crockett and Tubbs battled Miami’s drug vices on the screen, we’re reminded that the real-life city had to become awash in white powder. It was smuggled in by the likes of Mickey Munday (who hauled 10 tons of it),  distributed by the likes of Jon Roberts (two billion dollars-worth for the Medellin Cartel) and locally lorded over by Griselda Blanco and her personal “cowboy” assassin, Jorge “Rivi” Ayala. This came about as the undermanned Dade County police force fell prey to massive corruption, and the murder rate skyrocketed during what would become known as the Miami “cocaine wars.” The rampant violence and degradation made it into the Oliver Stone’s screenplay for 1983’s Scarface – a film which took a footnote in the 1980 Mariel Boatlift from Cuba and ran with it. Specifically, the opening title card informs us that “of the 125,000 refugees that landed in Florida an estimated 25,000 had criminal records.”

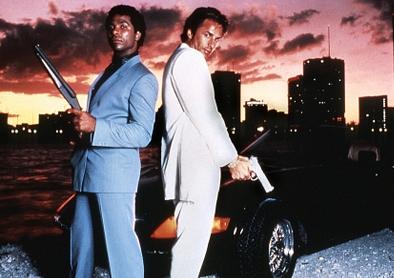

distributed by the likes of Jon Roberts (two billion dollars-worth for the Medellin Cartel) and locally lorded over by Griselda Blanco and her personal “cowboy” assassin, Jorge “Rivi” Ayala. This came about as the undermanned Dade County police force fell prey to massive corruption, and the murder rate skyrocketed during what would become known as the Miami “cocaine wars.” The rampant violence and degradation made it into the Oliver Stone’s screenplay for 1983’s Scarface – a film which took a footnote in the 1980 Mariel Boatlift from Cuba and ran with it. Specifically, the opening title card informs us that “of the 125,000 refugees that landed in Florida an estimated 25,000 had criminal records.”  Among them is one Tony Montana, who founds a cocaine-dealing empire in Miami with the help of extreme violence and a corrupt police force. We’re presented with an immigrant criminal who quickly achieves his American dream of money, power and women – and with utter disdain for fellow Cubans working honest lower-wage jobs. Miami is presented as a lawless seaside boomtown where police must work on the criminal’s level if they hope to compete, and Miami Vice spent five seasons with two undercover cops doing just that. The show’s opening credits feature palm trees, flamingos, wind surfing, cleavage, jai alai and stock car racing before ever throwing in a shot of the Miami skyline (whose construction was indirectly financed by cocaine money) – with an immediate cut to a speeding luxury sports car.

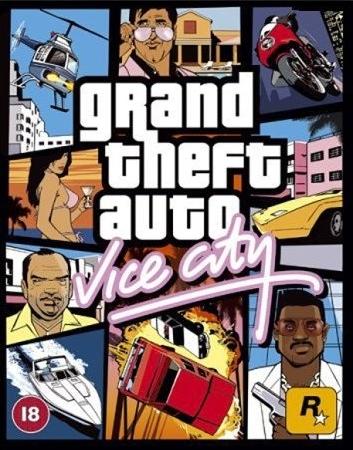

Among them is one Tony Montana, who founds a cocaine-dealing empire in Miami with the help of extreme violence and a corrupt police force. We’re presented with an immigrant criminal who quickly achieves his American dream of money, power and women – and with utter disdain for fellow Cubans working honest lower-wage jobs. Miami is presented as a lawless seaside boomtown where police must work on the criminal’s level if they hope to compete, and Miami Vice spent five seasons with two undercover cops doing just that. The show’s opening credits feature palm trees, flamingos, wind surfing, cleavage, jai alai and stock car racing before ever throwing in a shot of the Miami skyline (whose construction was indirectly financed by cocaine money) – with an immediate cut to a speeding luxury sports car. Later, we see the Atlantis Condominium, with its five-story hole and red spiral staircase, but the show focuses far more on the luxurious yachts and clubs inhabited by Miami’s drug and prostitution kingpins. This memorably stylized approach would later produce “Vice City” in the Grand Theft Auto video game series, which sets the action in the mid-1980’s and celebrates the street-level violence, fashion sense and New Wave sound motifs found in Scarface and Miami Vice. Recently, though, several Miami-set television programs have framed their look around the city’s reputation for beachside luxury. The promos for Burn Notice incorporate so many slow-motion glamour shots without visual exposition that it actually spawned a Saturday Night Live sketch wherein contestants compete on a game show called

Later, we see the Atlantis Condominium, with its five-story hole and red spiral staircase, but the show focuses far more on the luxurious yachts and clubs inhabited by Miami’s drug and prostitution kingpins. This memorably stylized approach would later produce “Vice City” in the Grand Theft Auto video game series, which sets the action in the mid-1980’s and celebrates the street-level violence, fashion sense and New Wave sound motifs found in Scarface and Miami Vice. Recently, though, several Miami-set television programs have framed their look around the city’s reputation for beachside luxury. The promos for Burn Notice incorporate so many slow-motion glamour shots without visual exposition that it actually spawned a Saturday Night Live sketch wherein contestants compete on a game show called “What is burn notice?” The most memorable recurring set piece for CSI: Miami are David Caruso’s designer sunglasses, followed by The Who screaming over an opening shot of the silhouetted downtown skyline. Nip/Tuck relied on its audience equating Miami with shallow aesthetic luxury during the four seasons it spent following two local plastic surgeons – that is, until season five, when it upped the ante by making the logical move to the even-more-decadent TV setting of Los Angeles. The series also features drug lord Escobar Gallardo, whose brazenness is reminiscent of Tony Montana.

“What is burn notice?” The most memorable recurring set piece for CSI: Miami are David Caruso’s designer sunglasses, followed by The Who screaming over an opening shot of the silhouetted downtown skyline. Nip/Tuck relied on its audience equating Miami with shallow aesthetic luxury during the four seasons it spent following two local plastic surgeons – that is, until season five, when it upped the ante by making the logical move to the even-more-decadent TV setting of Los Angeles. The series also features drug lord Escobar Gallardo, whose brazenness is reminiscent of Tony Montana.  An aspect of Dexter, meanwhile, echoes Miami Vice plot-wise with the inability of local police to stop Miami’s truly dangerous criminals (serial killers, here), except by means of someone who works on their level. The Birdcage portrays a far less violent Miami within the coastal house of a prosperous South Beach drag club owner, while the retirement setting of The Golden Girls is even more innocuous. Yet it’s popularity has failed to dull the lasting impression of Miami as the big screen’s most dangerous southern locale.

An aspect of Dexter, meanwhile, echoes Miami Vice plot-wise with the inability of local police to stop Miami’s truly dangerous criminals (serial killers, here), except by means of someone who works on their level. The Birdcage portrays a far less violent Miami within the coastal house of a prosperous South Beach drag club owner, while the retirement setting of The Golden Girls is even more innocuous. Yet it’s popularity has failed to dull the lasting impression of Miami as the big screen’s most dangerous southern locale.

3 minutes read

Miami, Florida

3 minutes read